Modern design and Alan Kay

published 2014-04-25 [ home ]

I have long been thinking that there is something wrong with modern product design thinking. I see designs that trade off almost all power, flexibility and composability for a smoother learning curve. I see designs that remove explicit controls and replace them by magic, choosing to hide essential complexity instead of reducing accidental complexity. I see designs optimized for new users and prospects instead of regular users, and designers who apparently consider documentation as something evil.

I do not like that trend. Learning from a community where RTFM was often the right answer has been very beneficial to me when I was a child. I am also a proponent of simplicity and complexity without complication, as should be obvious from the quotes I have been collecting over the last years.

The name of Alan Kay can be found a few times in this file, and so I was very pleased to find out that he recently gave a talk where he puts words on that hard-to-describe feeling: that this design school, which postulates that educating users is a bad idea and that everything should be natural, is hindering progress.

I found it so spot on that I decided to transcribe part of it below. I encourage you to read, and then watch the whole video if you can!

Human beings tend to hate learning curves, […] and marketing people really hate learning curves. […]

Any product today that requires a substantial learning curve is not what marketing people are looking for. As the joke goes, they want a brand new idea that has been perfectly tested. They would like something that people instantly recognize, but you’re the only person who has it. So they want something, essentially, that would have appealed to any cave person 100000 years ago, something that fits into what our genes set us up to be interested in.

An interesting question is: if the bicycle were invented tomorrow, would it actually be carried through? Think of how dangerous a bicycle is, think of the lawsuits! The bicycle is only tolerated today because it has been around for a long time, when people didn’t sue when a kid got danked.

Another way to look at it is that the larger world out there is kind of a low pass filter. And this is still going on: the iPad has a much more brain-dead interface than the Mac. […] If you think of the iPad as a gesture device, a gesture is inherently something that gives you not just naturalness but efficiency. And so when you’re doing gestures-oriented computing, and the origin of that goes back into the 60s - there were some really wonderful systems back then, what you really want to do is to learn a bunch of gestures to make you fluent and efficient on the thing. And the iPad doesn’t have any particular way of teaching you those gestures. They don’t force the developers to put a teaching thing for those gestures in there. And so basically everything is devolved down to the few simple gestures that are generic to the iPad.

This is kind of a dumb-down-ism that has been incredibly successful for people who are only interested in making money. It has not been good for personal computing. […]

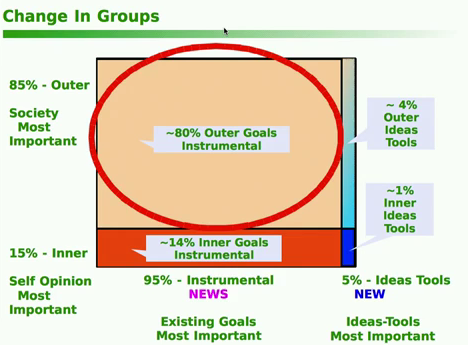

If we look at human psychometrics, […] when a new idea or tool appears, about 95% of us are what are called instrumental reasoners. […] And an instrumental reasoner is a person who judges the new idea or tool on whether it will advance their current goals. […] They are very conservative about shifting their goals. 5% of us are interested in the new idea or tool just because we’re interested in new ideas and tools, and many of these people actually change their goals when a new idea or tool appears.

If we look at the other axis, about 85% of us do things primarily for social approval. That’s what extroversion actually means: it doesn’t mean you’re a performer, it means you are actually interested in the opinions of others. About 15% of us are inner-directed.

If you combine these two (and I realize that they might not be completely independent dimensions, but they are independent enough for this talk) you get this interesting thing: 1% of us is inner-directed, not so interested in the approval of others, and intrinsically interested in new ideas and tools.

And 80% of us are goal-conservative, instrumental and directed by what our society thinks of us. This group requires almost everybody to agree on something before anybody agrees on something. […] So this group generally cannot do something just because it is a good idea. This is just not a concept that this group has, the majority of human beings. They’ll do something if it is actually part of a sanction. And so this group is capable of doing things that are terrible ideas […] if they’re sanctioned by the group. […]

And it turns out of you want to make a change in the larger world, you have to do something with the 80%. The 1% are more or less always with us and doing things. Some eras they get burnt at the stake, some eras they get rejected. In the 60s they actually got funded for a while. Xerox PARC came out of the funding of those people in the 60s, but they’re always with us.