A short introduction to Interval Tree Clocks

published 2017-05-07, updated 2024-11-24 [ home ]

This post is a rough transcription of a lightning talk I gave at dotScale 2017.

EDIT (2024-11-24): this post is on HN today. For people finding this now, Lima has shut down since then.

One of the things I work on at Lima is master-master filesystem replication. In this kind of system, we need to track causality. In a nutshell, given two events modifying a given piece of data and originating from different nodes in the system, we want to know if one of those events could have influenced the other one, or in other words if one of those events “happened before” the other one.

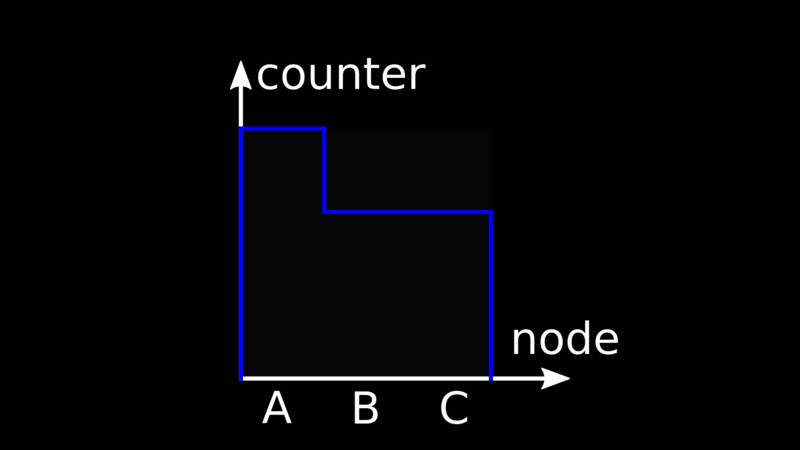

To do that, we use constructs such as Version vectors. The idea is that we give each node in the system a globally unique identifier, and we associate it to a counter.

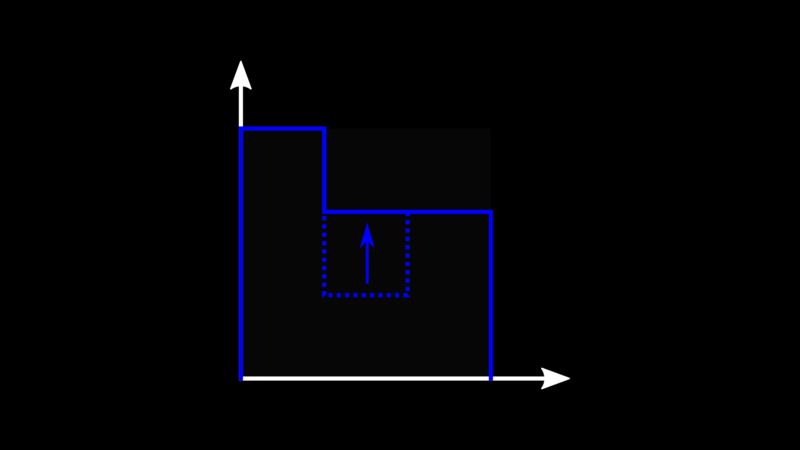

When an event modifying data on a node occurs, we increment the local value of the corresponding counter by one.

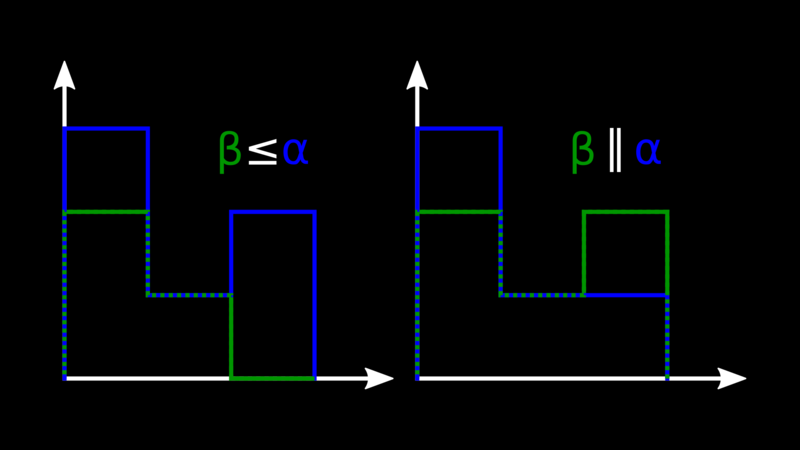

Version Vectors are partially ordered. Given two vectors, if we can find one such that, for every node, its counter is higher than the other one, then we say it descends the other one, meaning the related event “happened after” the other one. Otherwise, we say that the vectors are concurrent, and typically that means we will probably have some kind of data conflict to solve.

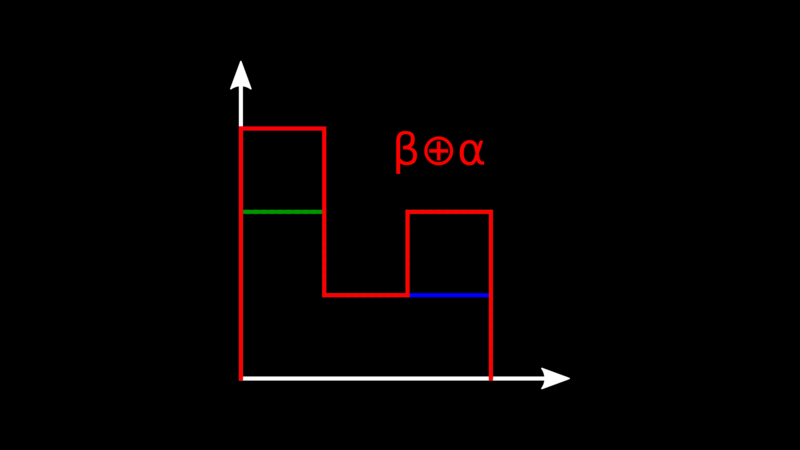

When we merge data changes we also merge the vectors, and to do so we take the maximum value of the counter for every node.

This works fine in most cases, but there is one case where it breaks down: highly dynamic systems experiencing a lot of churn. This means systems where nodes join the system, modify some data, then leave forever. The issue with such systems is that, even though there may not be a lot of active devices at any given point in time, the number of unique node identifiers in version vectors keeps increasing. We call that issue actor explosion.

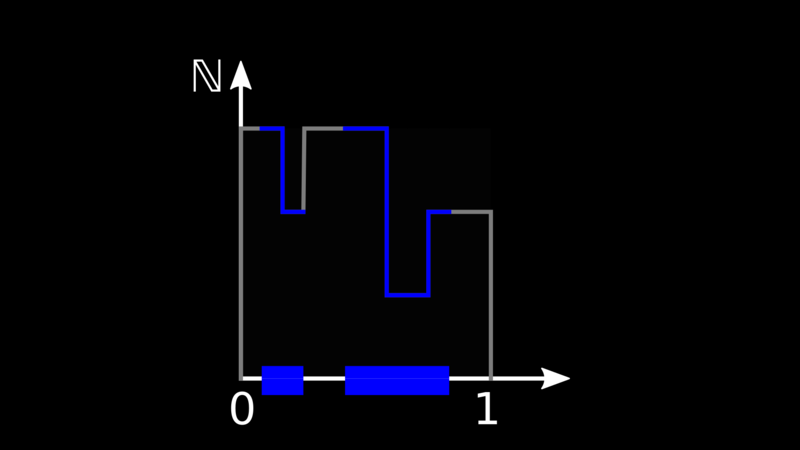

Interval Tree Clocks are an attempt to solve this problem. Instead of

giving a unique identifier to every node in the system, we take the

real-valued interval [0, 1] and attribute a part of it (not necessarily

contiguous) to every node. On top of it, we draw an integer-valued curve.

We call the combination of the interval share and the curve a stamp.

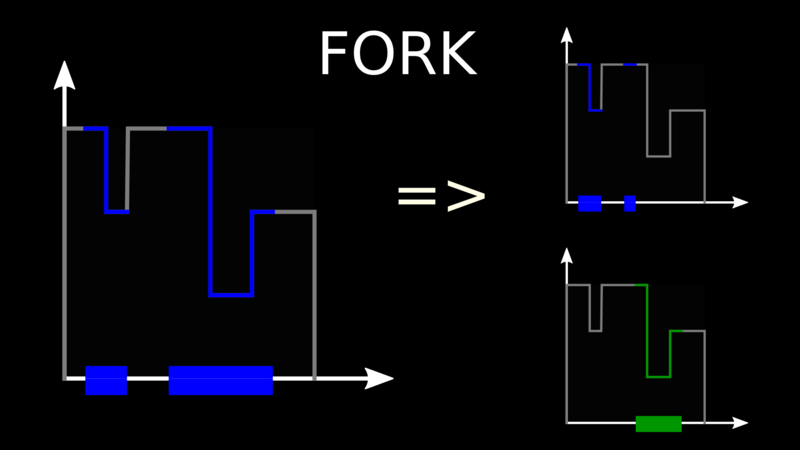

To add a new node to the system, we start from an existing node and we fork it, meaning we give part of its share of the interval to the new node.

When an event occurs on a node, it increases the height of the curve of its copy of the stamp anywhere within its share of the interval. Comparison works similarly to Version Vectors: if the curve of a stamp is above the other one, it descends it, otherwise the curves intersect and the stamps are concurrent.

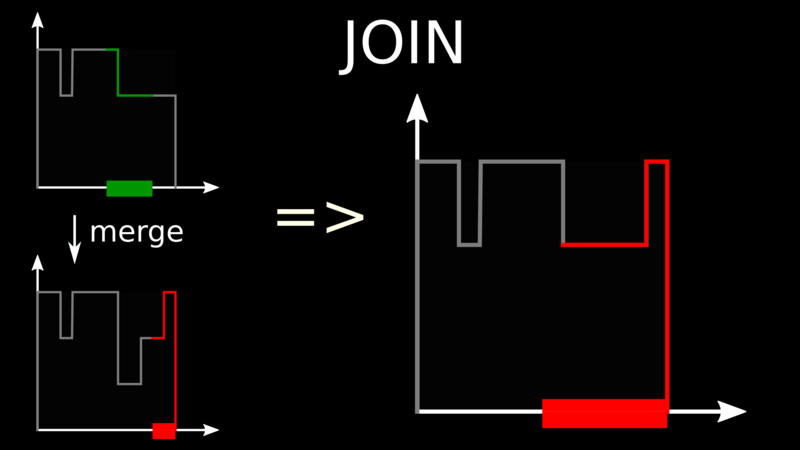

When a node wants to leave the system, it merges back with any other node and surrenders its share of the interval. To merge, we just take the maximum curve.

The beauty of this scheme is that a node only has to know about its share of the interval, not information about all other nodes. There are no globally unique node identifiers.

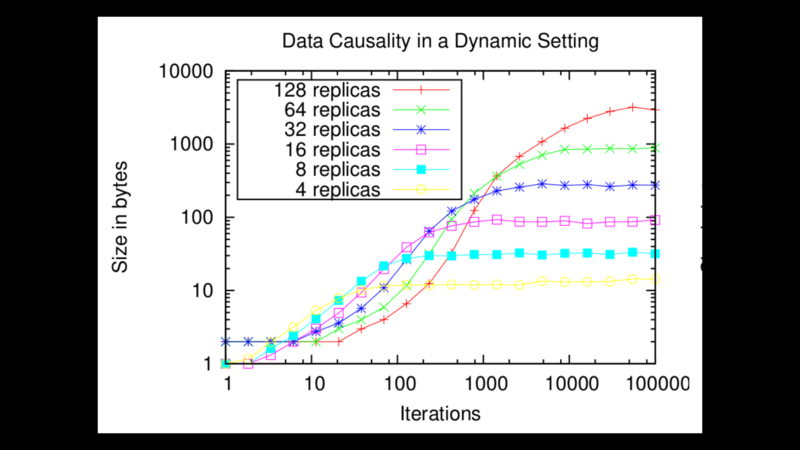

If we choose how we increase the height of the curve when an event occurs in a clever way which I will not detail here, we can ensure the complexity of the curve remains low. We can then encode it efficiently using a tree-shaped data structure and a custom binary format, with a size that depends more on the number of nodes interacting with the data at a given point in time than on the overall number of nodes which have touched it since inception.

If you want to know more, I encourage you to read the 2008 paper by Paulo Sérgio Almeida, Carlos Baquero and Victor Fonte; it is one of the best I know on the topic of causality. You can also check out my Lua implementation of ITC or one of the other implementations linked in the README.

EDIT (2024-11-24): other interesting resources are this slide deck by Carlos Baquero and those posts by Fred Hebert.